What does Grooming a Horse & Using Photoshop Have in Common?

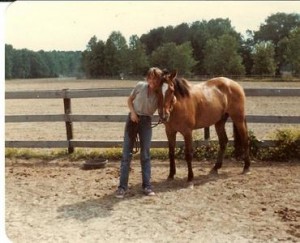

When I was young, I was wild about horses. There was a horse ranch in my area that also served as a summer camp, and gave riding lessons on Saturdays in the other seasons. I learned horseback riding there when I was just a wee one, and as a teenager taught horseback riding at all levels to children & adults. I didn’t realize how cool that was until years later. I didn’t get paid much for it, but I was a 14-year-old teaching adults how to ride horses without killing themselves. Why didn’t anyone tell me how cool that was? But that’s another entry for another day.

When I was young, I was wild about horses. There was a horse ranch in my area that also served as a summer camp, and gave riding lessons on Saturdays in the other seasons. I learned horseback riding there when I was just a wee one, and as a teenager taught horseback riding at all levels to children & adults. I didn’t realize how cool that was until years later. I didn’t get paid much for it, but I was a 14-year-old teaching adults how to ride horses without killing themselves. Why didn’t anyone tell me how cool that was? But that’s another entry for another day.

I ended up working at this ranch in various capacities at different times. In addition to teaching horseback riding and leading trail rides, I spent time assisting counselors and swim instructors in the summer, feeding and medicating horses, cleaning saddles and other tack, scooping horse poop (of course), and mucking stalls. But my favorite task at the ranch was grooming. Often, we would take horses out on muddy trails, and when they returned from these ventures, that was my favorite time to groom. It was extremely satisfying to take a mud-caked beast and turn her into a beautiful horse with soft, shiny fur and a flowing mane and tail. I could spend hours alone with an animal in a stall grooming him to perfection. If my cohorts couldn’t find me, they knew to check the stalls. If I wasn’t in a stall grooming, I would probably be in the tack room transforming a saddle with saddle soap, leather conditioner, and elbow grease.

I didn’t over think things then, so I didn’t realize why I loved these tasks so much, but now that I do over think, it seems that everything I’ve ever loved to do – truly loved, not thought I loved due to false motivations, as will happen – goes back to that core experience of, and desire for, transformation, of turning nothing into something. It is a romantic and simple notion. It is the push behind every creative effort. It makes me realize that even when I didn’t know and didn’t care, I was creative. This realization expanded my ideas about creativity a hundredfold.

Now I’m going to connect this to something more timely: Photoshop. Photoshop is one of the most powerful tools a photographer has to achieve transformation. It is only a tool, yet somehow it gets a lot of people into a tizzy. Yesterday, for the umpteen millionth time, I saw a gorgeous work of art on Facebook being maligned in the comments because the artist had used Photoshop as one of his tools. There are so many layers of perplexing attitudes embedded in this phenomenon that it deserves some peeling back.

Let’s put the moral issue to bed right away, shall we? Let’s be clear that when we are talking about a work of art, there’s NO moral dilemma in plucking a beautiful moon shot from one picture and compositing it with a mountain scene, say, or shining down on the statue of liberty. If a painter were to paint the same scene, there would be no complaints of it not being “real.” Of course it’s not “real.” It’s art! Art, by its very nature, is an amalgam of reality and fantasy, the conscious and the subconscious. As E.M. Forster once put it, in a state of inspiration, a person “lets down… a bucket into his subconscious, and draws up something which is normally beyond his reach. He mixes this thing with his normal experiences and out of the mixture he makes a work of art.” So, if you can tell a photo has been worked on and you don’t like it, don’t do it. Don’t buy it. Don’t “like” it. But don’t malign someone else’s aesthetic or creative process, or the tools that she chooses to use in order express herself.

What would be a moral problem is if a photographer put a gun in the hand of a suspect when it hadn’t been there, or somebody photoshopped a bong into the hands of a politician. In general, photojournalists have a finer line to walk than the rest of us, but barring those situations, where accurate documentation is of the utmost importance, I ask you: so what?

But the morality issue cannot be put to bed without at least acknowledging the phenomenon of advertising, and this is where things get messy. I suppose the mixing of art and commerce is messy almost by necessity, or at least messiness is inevitable. The main thing I’m thinking about here is the very real problem of the perceived pressure on girls – and all of us, really, but especially girls – to conform to some ideal of beauty that is in reality achieved by Photoshop. I freely admit that I am stymied by this one. I acknowledge that it happens and that it can be destructive, but I also know there’s very little beyond financial pressure that can turn it around. The short version of what I think (and perhaps this specific topic deserves its own post someday) is that this can be averted by changing the way we raise girls, and the messages that we as parents, teachers, family members, and friends convey. I know it’s less than adequate, but this post happens to be about art, and I consider this the misuse of a tool, not evidence that the tool itself is corrupt.

Now, on to photographers who say that“real” photographers get it “right” in camera. First of all is the obvious: what’s “right”? Whose version of right should we go with here? My thought when I hear this is that people who espouse it are in truth espousing a kind of documentary, non-creative approach to photography, but even then perceptions differ. Many who hold this attitude, furthermore, are – I’m sorry to say – a little older (but not more mature) and are perhaps displaying the resistance to technology for which their ilk is famous. I think of this type of person in the same group as those who won’t let go of film or vinyl, and assert that the world is coming to an end because others have let go of them. Sigh. The sky is not falling, Henny Penny!

As a photographer who wants to get it “right” in camera, does that mean leaving your camera on auto and allowing it to “objectively” record what you point it at? If not, what does it mean, exactly? If you are one of these, I would love for you to speak your truth in the comments. If I like high key images, and expose for that, is that getting it right, or is that just another way to manipulate the scene, or is it just an overexposed photo? Well, it is another way to manipulate the outcome, but I’m trying to figure out the difference between manipulating in camera and manipulating after the fact. Since the sentiments of many of those who espouse getting it “right” in camera (I’m sorry; I can’t help but put it in quotes) have the tone of judgment and superiority, I have tried to figure out why, and I just can’t come up with a logical reason.

I can understand people having aesthetic objections to certain forms of manipulation. I think this falls under the umbrella of everybody has different tastes, and if you don’t like it leave it alone. But there’s also the argument that, in fact, manipulations of various kinds can help us render the scene more realistically, more like the way our eyes saw it. As anyone knows who has spent one minute using a camera, even if they have never taken it off Auto, even if they have no interest in photography as an art or a science, our cameras are just not as sophisticated as our eyes. Period. Is there anyone on the planet who hasn’t taken a photo, whether intended to be a snapshot or a work of art, who hasn’t noticed that some photos just don’t look anything like the reality of the scene? Even putting your camera on Manual and adjusting the exposure is a manipulation. Just as a few adjustments could transform a beast back into a glistening beauty of a horse, so too can a few adjustments transform a scene into what we actually saw with our eyes. I know the word manipulation has a negative connotation, but I hope for that to change. Like Photoshop, it is a tool. Without manipulation, there is no hope for transformation. Without transformation, there is no hope for art or creativity. Without art, there is no hope for humanity.

I leave you with some simple edits to contemplate. I used Lightroom for these, not even Photoshop, but they show how simple edits can make a big difference in what the viewer perceives. Please click on each one to see them properly.

Tracey Mershon

Tracey Mershon